Filling radius

In Riemannian geometry, the filling radius of a Riemannian manifold X is a metric invariant of X. It was originally introduced in 1983 by Mikhail Gromov, who used it to prove his systolic inequality for essential manifolds, vastly generalizing Loewner's torus inequality and Pu's inequality for the real projective plane, and creating Systolic geometry in its modern form.

The filling radius of a simple loop C in the plane is defined as the largest radius, R>0, of a circle that fits inside C:

Contents |

Dual definition via neighborhoods

There is a kind of a dual point of view that allows one to generalize this notion in an extremely fruitful way, as shown by Gromov. Namely, we consider the  -neighborhoods of the loop C, denoted

-neighborhoods of the loop C, denoted

As  increases, the

increases, the  -neighborhood

-neighborhood  swallows up more and more of the interior of the loop. The last point to be swallowed up is precisely the center of a largest inscribed circle. Therefore we can reformulate the above definition by defining

swallows up more and more of the interior of the loop. The last point to be swallowed up is precisely the center of a largest inscribed circle. Therefore we can reformulate the above definition by defining  to be the infimum of

to be the infimum of  such that the loop C contracts to a point in

such that the loop C contracts to a point in  .

.

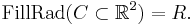

Given a compact manifold X imbedded in, say, Euclidean space E, we could define the filling radius relative to the imbedding, by minimizing the size of the neighborhood  in which X could be homotoped to something smaller dimensional, e.g., to a lower dimensional polyhedron. Technically it is more convenient to work with a homological definition.

in which X could be homotoped to something smaller dimensional, e.g., to a lower dimensional polyhedron. Technically it is more convenient to work with a homological definition.

Homological definition

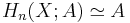

Denote by A the coefficient ring  or

or  , depending on whether or not X is orientable. Then the fundamental class, denoted [X], of a compact n-dimensional manifold X, is a generator of the homology group

, depending on whether or not X is orientable. Then the fundamental class, denoted [X], of a compact n-dimensional manifold X, is a generator of the homology group  , and we set

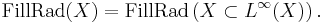

, and we set

where  is the inclusion homomorphism.

is the inclusion homomorphism.

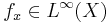

To define an absolute filling radius in a situation where X is equipped with a Riemannian metric g, Gromov proceeds as follows. One exploits an imbedding due to Kazimierz Kuratowski (the first name is sometimes spelled with a "C"). One imbeds X in the Banach space  of bounded Borel functions on X, equipped with the sup norm

of bounded Borel functions on X, equipped with the sup norm  . Namely, we map a point

. Namely, we map a point  to the function

to the function  defined by the formula

defined by the formula  for all

for all  , where d is the distance function defined by the metric. By the triangle inequality we have

, where d is the distance function defined by the metric. By the triangle inequality we have  and therefore the imbedding is strongly isometric, in the precise sense that internal distance and ambient distance coincide. Such a strongly isometric imbedding is impossible if the ambient space is a Hilbert space, even when X is the Riemannian circle (the distance between opposite points must be π, not 2!). We then set

and therefore the imbedding is strongly isometric, in the precise sense that internal distance and ambient distance coincide. Such a strongly isometric imbedding is impossible if the ambient space is a Hilbert space, even when X is the Riemannian circle (the distance between opposite points must be π, not 2!). We then set  in the formula above, and define

in the formula above, and define

Relation to diameter and systole

The exact value of the filling radius is known in very few cases. A general inequality relating the filling radius and the Riemannian diameter of X was proved in (Katz, 1983): the filling radius is at most a third of the diameter. In some cases, this yields the precise value of the filling radius. Thus, the filling radius of the Riemannian circle of length 2π, i.e. the unit circle with the induced Riemannian distance function, equals π/3, i.e. a sixth of its length. This follows by combing the diameter upper bound mentioned above with Gromov's lower bound in terms of the systole (Gromov, 1983). More generally, the filling radius of real projective space with a metric of constant curvature is a third of its Riemannian diameter, see (Katz, 1983). Equivalently, the filling radius is a sixth of the systole in these cases. The precise value is also known for the n-spheres (Katz, 1983).

The filling radius is linearly related to the systole of an essential manifold M. Namely, the systole of such an M is at most six times its filling radius, see (Gromov, 1983). The inequality is optimal in the sense that the boundary case of equality is attained by the real projective spaces as above.

See also

References

- Gromov, M.: Filling Riemannian manifolds, Journal of Differential Geometry 18 (1983), 1-147.

- Katz, M.: The filling radius of two-point homogeneous spaces. Journal of Differential Geometry 18, Number 3 (1983), 505-511.

- Katz, Mikhail G. (2007), Systolic geometry and topology, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, 137, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-4177-8, OCLC 77716978

|

|||||||||||

![\mathrm{FillRad}(X\subset E) = \inf \left\{ \epsilon > 0 \left|

\;\iota_\epsilon([X])=0\in H_n(U_\epsilon X) \right. \right\},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/81fcce6ccf099facdc9e95e8d1e3b28e.png)